Voters Give Abe an Opening for Constitutional Debate

This blog post is part of a series entitled Will Japanese Change Their Constitution?, in which leading experts discuss the prospects for revising Japan’s postwar constitution.

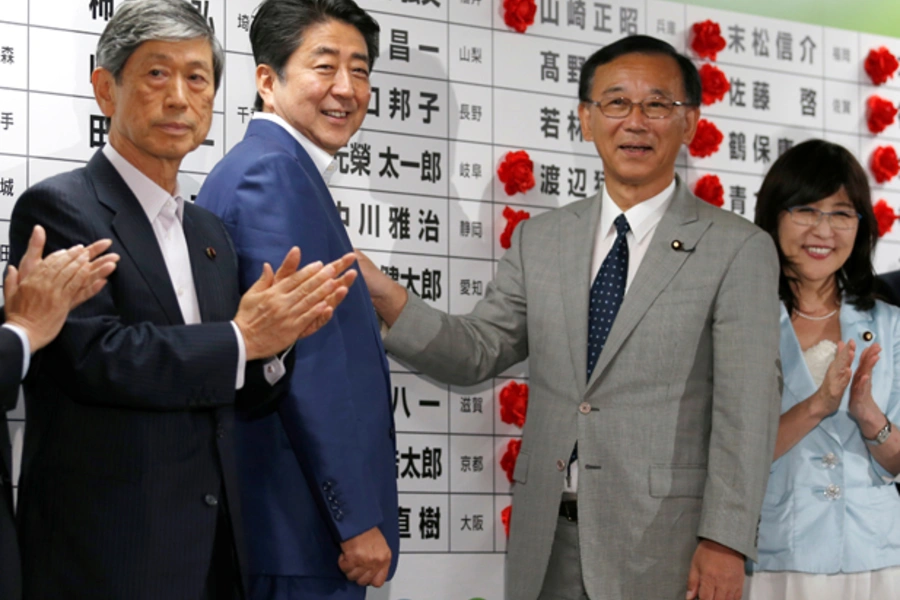

As elections go, yesterday’s Upper House vote was not a compelling display of popular interest in governance, yet it was an undeniable victory for the prime minister and his party. Voter turnout was only 54.7 percent, on the lower end of postwar Upper House election turnouts but larger than the last Upper House contest in 2013. But Japan’s younger voters gave their ruling party a boost. 40 percent of Japan’s newest voters, eighteen-and nineteen-year-olds, opted for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

More on:

All in all, it was a vote for the status quo – and for the government’s agenda. The LDP gained fifty-six seats, and the Komeito fourteen, for a total of seventy. The small Initiatives From Osaka (IFO or Osaka Ishin no Kai) also did well (seven seats, up five seats), adding to the pro-revision coalition. The opposition parties fared less well. Democratic Party (DP), a merger of the former Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) and the Japan Innovation Party, took thirty-two seats, but notably won 23 percent of the proportional representation vote giving the former DPJ the best outcome since it left office in 2012, suggesting that the party merger formed in March may have helped the embattled DPJ. The Japanese Communist Party (JCP) took six seats – no more, no less for the party most likely to veto government policy choices. While the effort to build an anti-Abe electoral backlash failed from preventing the ruling coalition to secure majority of contested seats, voter support in urban electorates at the end of the day for some opposition party candidates should be enough to give the ruling coalition pause.

Today, members of Japan’s 242-seat Upper House identify as follows: LDP 121; Komeito 25; DP 49; JCP 14; IFO 12; Party for Japanese Kokoro 3; Social Democratic Party (SDP) 2; People’s Life Party and Taro Yamamoto and Friends 2; Assembly to Energize Japan 2; ruling coalition affiliated independents 3; opposition parties affiliated independents 5; independents 3; and other 1.[1]

Abe has an electoral mandate but it is not clear how much wind he has beneath his sails for policy reform. While polling suggests Abe is on the right track with loyal voters, turnout in elections since he returned to office in 2012 reveals an undercurrent of apathy among the voters. The LDP’s campaign slogan says it all, “Let’s Move Japan Forward….” Few could argue with that. Who wants to go backwards? In policy terms, forward means more Abenomics, and a slightly suggestive pose on revising the constitution.

Yet it is hard to make the case that Abenomics has worked. The prime minister has tweaked his policy instruments a bit, backing away from raising the consumption tax (a good move if you want to attract votes as well as encourage consumption) and promising greater fiscal stimulus (again especially good for rural Japanese who are feeling the economic pain the most). The Bank of Japan governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, also seems to be poised to do just a bit more easing as well.

The prime minister sees constitutional revision also as portending a brighter future identity for Japanese. But few Japanese have a clear idea of what he means in practical terms. Last time there was an Upper House election, Abe argued for reducing the threshold for revision but that idea went nowhere. This time round rallying those who want a debate seems to have worked. A beaming Abe in the evening hours yesterday suggested that the LDP draft could become the basis of a broader discussion among all political parties. Speaking with a popular journalist, Akira Ikegami, during the live election coverage on TV Tokyo, Abe pointed out that,

More on:

Our party has already demonstrated our desire to change Article Nine and Article Ninety-six. But we want to go beyond those articles, to revise it all - including the preamble. But politics is the art of realizing goals. Without a two-thirds majority, it seems useless to debate how to reform the constitution or which articles to rewrite.[2]

Clearly, Japanese voters have yet to sign up for any particular version of a new constitution, and exit polling revealed a confusing picture. NHK exit polling found 33 percent for, 32 percent against, and 36 percent uncertain, while remarkably, the liberal Asahi Shimbun reported 49 percent for revision and 44 percent against in its exit polling.

Nine political parties went into this election, but not all ended up with seats in the Upper House. Virtually all had some sort of position on the constitution, and interestingly newer parties that defined themselves solely in terms of the revision debate – pro or con – got little traction with Japanese voters.

| Party Name | Seats up for Reelection[3] | Seats Won | Position on Constitution |

| Party for Japanese Kokoro | 0 | 0 | Pro revision. Aims to implement our own Constitution that reflects our long history and tradition and our custom and mind. |

| Liberal Democratic Party | 50 | 56 | Pro revision. Seeks to conduct thorough debates in Commission on Constitution in both Houses, cooperate with the opposition parties, and gain consensus from the citizens |

| Initiatives from Osaka | 2 | 7 | Pro revision. Revise constitution to introduce free education, constitutional court, and institutional reform and more regional sovereignty. |

| Komeito | 9 | 14 | No mention in manifesto |

| New Renaissance Party | 1 | 0 | It is too soon for constitutional amendment. |

| Democratic Party | 45 | 32 | Opposed to revising Article Nine; Aims to plan a constitution that is future-oriented with the cooperation from the people. |

| People’s Life Party and Taro Yamamoto and Friends | 2 | 1 | Respects the concept of constitution under the principles of national sovereignty, basic human rights, and pacifism. |

| Social Democratic Party | 2 | 1 | Prevent revision of existing pacifist constitution. |

| Japanese Communist Party | 3 | 6 | Prevent any revision, including the preamble. |

* All English renditions of political party names are taken from official websites.

While the headlines focus on the pro-revision winners, those who lost on an anti-revision platform also deserve attention. For example, the SDP, a longstanding opponent of the LDP on its interpretation of the constitution, lost an important representative— Tadatomo Yoshida, the party head— leaving only four members serving in the Upper and Lower Houses. A newer party, the Voice of Citizen’s Anger, led by Setsu Kobayashi, one of the expert constitutional scholars called to testify last summer in the Diet, did not win any seats. The People’s Life Party and Taro Yamamoto and Friends, led by Ichiro Ozawa, also lost a seat, leaving only two seats in both Houses of the diet.

Yet in the game of numbers, this Upper House election brings the prospect of a revision process into the realm of the possible. Virtually every media yesterday added up the Upper House legislators that could be described as pro-revision, both those (re) elected on Sunday and those who were not up for reelection. The widely accepted consensus is that for the first time in the postwar era, both houses of parliament have the requisite two-thirds majority to initiate a debate on constitutional revision.

So if we are heading toward a debate over the Japanese constitution, what will that debate look like?

Prior to Sunday’s election, I asked four Japanese politicians to share their thoughts on how this Japanese debate might proceed: on the pro-revision side, two LDP legislators, Kazuo Aichi and Hajime Funada, who have held responsibility for crafting their party’s position; Secretary General of the Komeito Natsuo Yamaguchi, who will provide his thoughts on how to build a consensus from the unique vantage point of being in the current ruling coalition but opposed to/cautious on revision; and, finally, Satsuki Eda, chair of the DP’s Research Committee on the Constitution and a longstanding advocate of protecting Japan’s current constitution.

[1] As of July 11, 4:00 p.m. EST, the Upper House has yet to announce official results of this election, therefore we are relying on media reports. These numbers are from the Asahi Shimbun, and Nikkei and NHK also report the same numbers. The Yomiuri Shimbun reports that the LDP won fifty-five seats as Kenji Nakanishi ran as an independent and was later recognized as a LDP member.

[2] “TXN Senkyo SP Ikegami Akira no saninsen raibu” [TXN Election Special: Akira Ikegami’s Live Coverage on Upper House Election], TV Tokyo, July 10, 2016, 7:50 p.m.

[3] These numbers are taken from the official website of the House of Councillors.

Online Store

Online Store